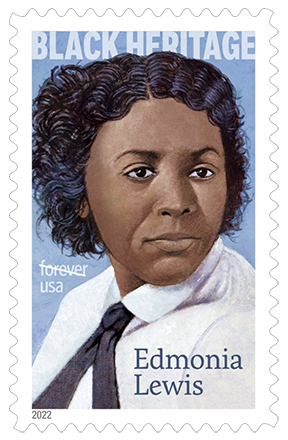

Mary Edmonia Lewis - The Death of Cleopatra

In 2022 Edmonia Lewis was honored by the United States Postal Service (USPS) with a stamp featuring her portrait painted by Alex Bostic. In a statement, the USPS said: “As the public continues to discover the beautiful subtleties of Lewis’s work, scholars will further interpret her role in American art and the ways she explored, affirmed or de-emphasized her complex cultural identity to meet or expand the artistic expectations of her day."

Notable Black Proviso Community Members

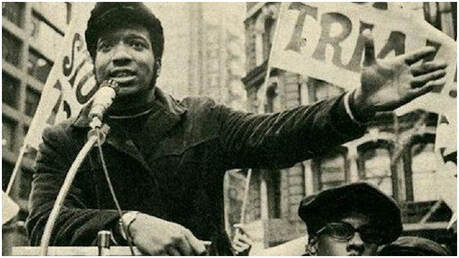

Fred Hampton

Fred Hampton was born in Chicago on August 30, 1948 and his family moved to Maywood, IL when he was ten. He attended Proviso East High School where he gained early experience in organizing. Seeing that Black students had few options if they were struggling academically, he worked to provide more counseling resources. He pushed for adding more Black teachers to the faculty and administration, and his efforts were successful. Because only white girls were allowed to run for Homecoming Queen, he organized a boycott of the Homecoming Dance and a student walkout, The result was the election of the school’s first black Homecoming Queen. He was a gifted and persuasive speaker and well-liked by both teachers and students. He graduated high school with honors.

He studied pre-law at Triton Community College and became active in the NAACP, leading the West Suburban branch of their Youth Council and increasing their membership to over 500 members.

Hampton joined the Black Panther Party and moved to Chicago, where his leadership, charisma, and speaking skills quickly became apparent. Hampton formed the “Rainbow Coalition,” a group comprised of the Black Panthers, the Young Patriots, the Young Lords, and Chicago street gangs. He led them to stop infighting and work together for social change.

Hampton rose to head up the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party, organizing rallies and coordinating with the People’s Clinic and the Free Breakfast Program. He soon attracted the attention of the FBI’s illegal surveillance program COINTELPRO, whose goal was to infiltrate, discredit, and disrupt leftist American political organizations. The FBI hired a criminal informant, William O’Neal, to infiltrate the Black Panther Party and win Hampton’s confidence. O’Neal became Fred Hampton’s bodyguard and helped create rifts between the parties of the Rainbow Coalition that Hampton had built.

On December 3, 1969, O’Neal slipped Hampton a strong sleeping drug into his drink and then left the apartment. That night officers raided Hampton’s apartment and opened fire while he and his pregnant fiancée were asleep. Police fired 99 shots while the Panthers only shot twice. After finding that Hampton was still alive, one of the officers shot him twice in the head and killed him. Mark Clark, who was present as a bodyguard, was also killed.

Shortly after, a break-in at an FBI field office in Philadelphia brought to light FBI plans to assassinate Hampton. In 1970 Hampton’s family sued for $47.7 million in a civil rights case. In 1982, Cook County and the U.S. government agreed to a settlement of $1.85 million.

Sources:

National Archives: https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/individuals/fred-hampton#:~:text=Fred%20Hampton,law%20at%20Triton%20Junior%20College.

Howard Zinn: A People’s History of the United States

He studied pre-law at Triton Community College and became active in the NAACP, leading the West Suburban branch of their Youth Council and increasing their membership to over 500 members.

Hampton joined the Black Panther Party and moved to Chicago, where his leadership, charisma, and speaking skills quickly became apparent. Hampton formed the “Rainbow Coalition,” a group comprised of the Black Panthers, the Young Patriots, the Young Lords, and Chicago street gangs. He led them to stop infighting and work together for social change.

Hampton rose to head up the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party, organizing rallies and coordinating with the People’s Clinic and the Free Breakfast Program. He soon attracted the attention of the FBI’s illegal surveillance program COINTELPRO, whose goal was to infiltrate, discredit, and disrupt leftist American political organizations. The FBI hired a criminal informant, William O’Neal, to infiltrate the Black Panther Party and win Hampton’s confidence. O’Neal became Fred Hampton’s bodyguard and helped create rifts between the parties of the Rainbow Coalition that Hampton had built.

On December 3, 1969, O’Neal slipped Hampton a strong sleeping drug into his drink and then left the apartment. That night officers raided Hampton’s apartment and opened fire while he and his pregnant fiancée were asleep. Police fired 99 shots while the Panthers only shot twice. After finding that Hampton was still alive, one of the officers shot him twice in the head and killed him. Mark Clark, who was present as a bodyguard, was also killed.

Shortly after, a break-in at an FBI field office in Philadelphia brought to light FBI plans to assassinate Hampton. In 1970 Hampton’s family sued for $47.7 million in a civil rights case. In 1982, Cook County and the U.S. government agreed to a settlement of $1.85 million.

Sources:

National Archives: https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/individuals/fred-hampton#:~:text=Fred%20Hampton,law%20at%20Triton%20Junior%20College.

Howard Zinn: A People’s History of the United States