Forest Park is located on the indigenous homelands of several tribal nations: the Kickapoo, Peoria, Kaskaskia, Potawatomi, Myaamia, and Ochethi Sakowin. We acknowledge the painful forced removal of these people from their ancestral lands by European settlers. We commit to building relationships with descendants of these tribal nations who still call this area home and to sharing the history and contributions of native peoples with the Forest Park community.

About Land Acknowledgment Statements

A land acknowledgment statement grounds a community by providing a sense of its full history. It keeps us from taking for granted the foundation of our lives: the land on which we live.

Why is indigenous land acknowledgment important?

“It is important to understand the longstanding history that has brought you to reside on the land, and to seek to understand your place within that history. Land acknowledgements do not exist in a past tense, or historical context: colonialism is a current ongoing process, and we need to build our mindfulness of our present participation.”

http://www.lspirg.org/knowtheland

How to pronounce the names of the tribal communities mentioned in our land acknowledgment statement:

Kickapoo (KEE-kah-poy)

Peoria (pea-OR-ee-ah

Kaskaskia (kahs-KAHS-kee-ah)

Potawatomie (pah-tuh-WAH-tuh-mee)

Myaamia (me-YAH-me-ah)

Ochethi Sakowin (Oh-CHET-ee-sha-KOH-win) meaning Seven Council Fires

Why is indigenous land acknowledgment important?

“It is important to understand the longstanding history that has brought you to reside on the land, and to seek to understand your place within that history. Land acknowledgements do not exist in a past tense, or historical context: colonialism is a current ongoing process, and we need to build our mindfulness of our present participation.”

http://www.lspirg.org/knowtheland

How to pronounce the names of the tribal communities mentioned in our land acknowledgment statement:

Kickapoo (KEE-kah-poy)

Peoria (pea-OR-ee-ah

Kaskaskia (kahs-KAHS-kee-ah)

Potawatomie (pah-tuh-WAH-tuh-mee)

Myaamia (me-YAH-me-ah)

Ochethi Sakowin (Oh-CHET-ee-sha-KOH-win) meaning Seven Council Fires

Burial Mounds in Forest Home Cemetery

After Ferdinand Haase sold some of his land to the founders of Concordia Cemetery in the 1870s, the cemetery business seemed more profitable than a picnic grove for the land now known as Forest Home Cemetery.

The land, along the Des Plaines River, had burial mounds from the mound-building cultures of the people who lived here before European settlement. Archeologist Charles Kenicott of River Forest recorded many of the local area’s mounds and trails, and excavated the artifacts, silver, tools, jewelry and pottery. Those items were displayed in the cemetery office and later given to the Forest Park Public Library to be repatriated in 2019.

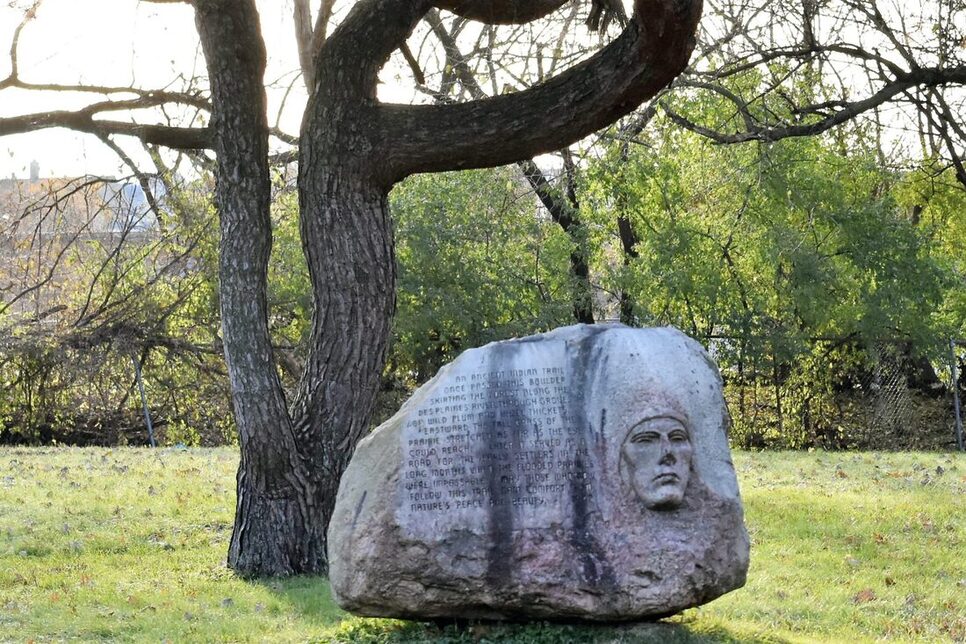

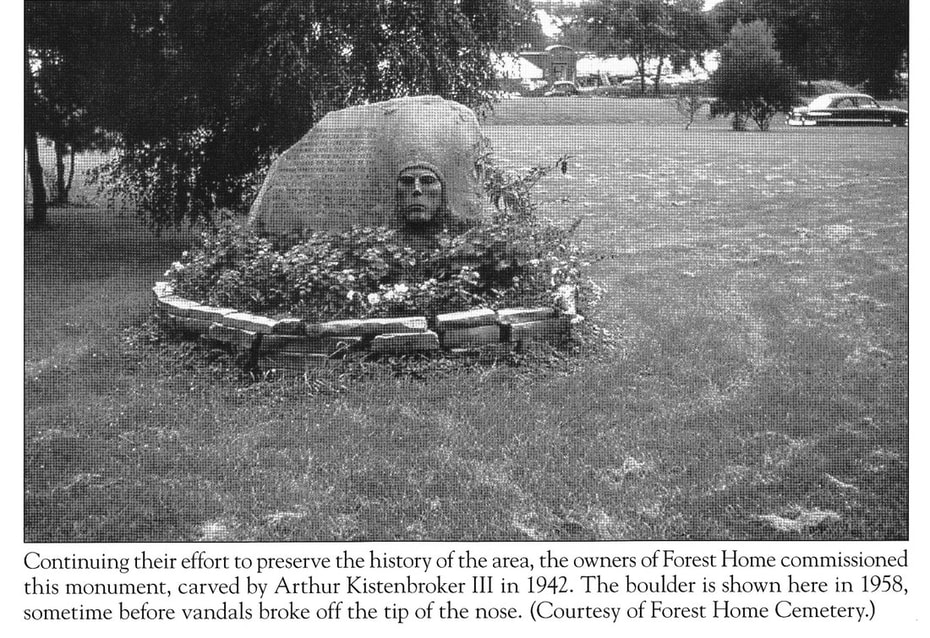

In 1941, the Haase family erected a statue on Indian Hill, a gathering place for the Potawatomi people. A year later, the family placed a large boulder with a carved face of a Potawatomi man at the trailhead found in section 27 of Forest Home Cemetery.

The land, along the Des Plaines River, had burial mounds from the mound-building cultures of the people who lived here before European settlement. Archeologist Charles Kenicott of River Forest recorded many of the local area’s mounds and trails, and excavated the artifacts, silver, tools, jewelry and pottery. Those items were displayed in the cemetery office and later given to the Forest Park Public Library to be repatriated in 2019.

In 1941, the Haase family erected a statue on Indian Hill, a gathering place for the Potawatomi people. A year later, the family placed a large boulder with a carved face of a Potawatomi man at the trailhead found in section 27 of Forest Home Cemetery.

Feedback

Thank you to everyone you submitted feedback during our open feedback period. We are taking your thoughtful comments into consideration and working up our statement.

Why aren’t there any federal Indian reservations in Illinois?

WBEZ Curious City

Unlike many states in the Midwest, including Michigan, Wisconsin and Iowa, Illinois doesn’t have any federally recognized Indian reservations. Yet all around the state, in the names of cities, rivers, streets and sports teams, there are reminders that we are living on land where Native Americans once farmed, traded and made their home.

By the time Europeans first explored the region in 1673, Native Americans had long been settled in villages all around the area.

So why aren’t there any reservations in Illinois?

The answer requires a look back at the region’s history from the late 1700s through the 1830s — a period marked by armed conflicts, numerous treaty negotiations often made under pressure and through coercive tactics, attempts by Native American leaders to reclaim their lands and a series of policies enacted by a U.S. government determined to push out Native peoples.

“The notion of land being commodified or being able to be owned by someone was really a foreign concept.”

— Patty Loew, Professor at Medill and Director of the Center for Native America and Indigenous Research at Northwestern University and Member of the Bad River Bad of Lake Superior Objibe with the help of John Low, associate professor at The Ohio State University and citizen of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians;

After settling first on a reservation in Iowa, the Potawatomi were later forced to move again. Many of their descendants now live as the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation in Kansas and the Citizen Band Potawatomi Nation in Oklahoma. Another group, the Forest County Potawatomi, have continued living in Wisconsin. They’re one of 11 federally recognized Indian nations and tribal communities in Wisconsin.

And thanks to a provision negotiated in the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi remains in southwest Michigan. That group sued Chicago in 1914, claiming ownership of the lakefront. The tribe argued that it never signed away this territory, which was created when landfill extended the city’s shoreline farther east. The U.S. Supreme Court rejected the tribe’s argument in a 1917 ruling.

“We shouldn’t be living guilt free on stolen land, right? And the point is not to make everybody guilt ridden. The point is to promote truth and reconciliation. And reconciliation comes through that, you know, that idea of well how can we make things right? How can we make amends for the taking of those lands? And it’s never too late to make amends.”

— John low, Associate Professor at The Ohio State University and Citizen of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians

The U.S. government sold the property in DeKalb County that had been set aside as Chief Shab-eh-nay’s reservation, claiming he’d abandoned it. The Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation says this land was stolen. U.S. Sen. Jerry Moran, a Kansas Republican, introduced a bill in November 2021 , that would recognize the site as a reservation. If it becomes law, the measure would also provide monetary compensation to the tribe for that land, and recognition of tribal government authority.

More resourcesJohn N. Low’s book Imprints: The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians and the City of Chicago

Ann Durkin Keating’s book Rising Up From Indian Country: The Battle of Fort Dearborn and the Birth of Chicago

Patty Loew’s book Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal

Kerry A. Trask’s book Black Hawk: The Battle for the Heart of America

The American Indian Center of Chicago, the country’s first urban Indian center, was found in 1953.

The Mitchell Museum of the American Indian in Evanston

The Center for Native American and Indigenous Research at Northwestern University

Explore 374 U.S. treaties with Indian tribes — and maps showing the lands involved in each treaty — at the Indigenous Digital Archive. The site includes a map showing all of the land ceded by the Potawatomi in various treaties with the U.S. government.

See an online dictionary of the Potawatomi language, also known as Bodwéwadmimwen, created by the Citizen Band Potawatomi Nation — and an app for learning the language.

Robert Loerzel is a freelance journalist and the author of Alchemy of Bones: Chicago’s Luetgert Murder Case of 1897. Follow him at @robertloerzel.

This timeline was produced for web using Timeline JS by Maggie Sivit, Curious City’s digital and engagement producer. Follow her @magisiv.

Unlike many states in the Midwest, including Michigan, Wisconsin and Iowa, Illinois doesn’t have any federally recognized Indian reservations. Yet all around the state, in the names of cities, rivers, streets and sports teams, there are reminders that we are living on land where Native Americans once farmed, traded and made their home.

By the time Europeans first explored the region in 1673, Native Americans had long been settled in villages all around the area.

So why aren’t there any reservations in Illinois?

The answer requires a look back at the region’s history from the late 1700s through the 1830s — a period marked by armed conflicts, numerous treaty negotiations often made under pressure and through coercive tactics, attempts by Native American leaders to reclaim their lands and a series of policies enacted by a U.S. government determined to push out Native peoples.

“The notion of land being commodified or being able to be owned by someone was really a foreign concept.”

— Patty Loew, Professor at Medill and Director of the Center for Native America and Indigenous Research at Northwestern University and Member of the Bad River Bad of Lake Superior Objibe with the help of John Low, associate professor at The Ohio State University and citizen of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians;

After settling first on a reservation in Iowa, the Potawatomi were later forced to move again. Many of their descendants now live as the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation in Kansas and the Citizen Band Potawatomi Nation in Oklahoma. Another group, the Forest County Potawatomi, have continued living in Wisconsin. They’re one of 11 federally recognized Indian nations and tribal communities in Wisconsin.

And thanks to a provision negotiated in the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi remains in southwest Michigan. That group sued Chicago in 1914, claiming ownership of the lakefront. The tribe argued that it never signed away this territory, which was created when landfill extended the city’s shoreline farther east. The U.S. Supreme Court rejected the tribe’s argument in a 1917 ruling.

“We shouldn’t be living guilt free on stolen land, right? And the point is not to make everybody guilt ridden. The point is to promote truth and reconciliation. And reconciliation comes through that, you know, that idea of well how can we make things right? How can we make amends for the taking of those lands? And it’s never too late to make amends.”

— John low, Associate Professor at The Ohio State University and Citizen of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians

The U.S. government sold the property in DeKalb County that had been set aside as Chief Shab-eh-nay’s reservation, claiming he’d abandoned it. The Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation says this land was stolen. U.S. Sen. Jerry Moran, a Kansas Republican, introduced a bill in November 2021 , that would recognize the site as a reservation. If it becomes law, the measure would also provide monetary compensation to the tribe for that land, and recognition of tribal government authority.

More resourcesJohn N. Low’s book Imprints: The Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians and the City of Chicago

Ann Durkin Keating’s book Rising Up From Indian Country: The Battle of Fort Dearborn and the Birth of Chicago

Patty Loew’s book Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal

Kerry A. Trask’s book Black Hawk: The Battle for the Heart of America

The American Indian Center of Chicago, the country’s first urban Indian center, was found in 1953.

The Mitchell Museum of the American Indian in Evanston

The Center for Native American and Indigenous Research at Northwestern University

Explore 374 U.S. treaties with Indian tribes — and maps showing the lands involved in each treaty — at the Indigenous Digital Archive. The site includes a map showing all of the land ceded by the Potawatomi in various treaties with the U.S. government.

See an online dictionary of the Potawatomi language, also known as Bodwéwadmimwen, created by the Citizen Band Potawatomi Nation — and an app for learning the language.

Robert Loerzel is a freelance journalist and the author of Alchemy of Bones: Chicago’s Luetgert Murder Case of 1897. Follow him at @robertloerzel.

This timeline was produced for web using Timeline JS by Maggie Sivit, Curious City’s digital and engagement producer. Follow her @magisiv.

Proudly powered by Weebly